August 1997 issue of the ABS magazine: "Interrupted Journey",

by Horst Ellenberger, of Nuremburg, Germany.

Horst recounts his first 360 attempt, ending in a ditching in the Pacific

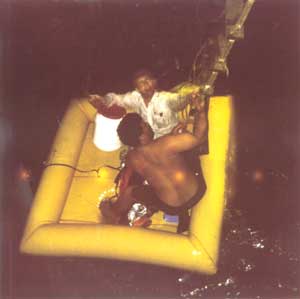

and his subsequent rescue.

Pacific Ocean for rescue crew to arrive.

Three friends - Jürgen Timm, Dr. Günter Kuhlmann, and I - set out to fly our V35 Bonanzas with long range equipment around the world. Jürgen had gone ahead via the Southern route of Dakar - Recife - Brazil and the Caribbean Sea to Chino near Los Angeles. Chino is a well-known home for 360° pilots, i. e. pilots who have flown around the world. Günter with his copilot Uwe and I and Jürgen (who had come back in the meantime) flew via Jersey to St. Maria on the Azores. The next day we set out to St. John's in Canada.

But two hours later we had to fly back because there was more head wind than anticipated and the higher fuel consumption would have made it impossible for us to reach our destination in Canada. The following day we refilled our airplanes and tried again. We underflew the jet stream, with 90 kt (approx.160 km/h) head wind and 60 kt (approx.105 km/h) on the nose. We covered a total distance of 1,740 NM, with an average head wind of 40 kt. St. John's reported poor weather with freezing rain or fog, and as the coast of Newfoundland is notorious for poor weather conditions at that time of the season, we had to fly to Sydney, our alternate, which was very good.

We then flew on to Chicago via Bangor for customs clearance, which surprisingly was done within 20 minutes. Our landing ground in Chicago was Du Page airport where we had the JA Air Center repair some electronic equipment. We also went to see E-T-A Chicago (my company) where we were given a warm welcome. When flying on to Pagosa Springs, Co, near the Rockies, we had to divert to Pueblo to get down because weather in front of us was getting worse so that even a metro liner nervously asked for an alternate.

Next morning, the weather was fine so we flew on to Pagosa where our turbocharger had been designed and produced. After having it thoroughly rechecked and improved, we spent the evening with Mary and Don Carpenter and other pilots mainly discussing the new GAMI fuel injectors.

There was overcast next morning, postponing the take-off, which had been scheduled for 1100. In Chino, our destination that day, they were waiting to have a party with us in the hangar of Dan Webb. At 1630 we finally arrived, heartily welcomed by our 360° friends. Next day we made a short jump to Santa Barbara, our departure airport for Honolulu where we prepared for the 2,175 NM flight with no possibility to land earlier. Since Chino, we were flying three V35B airplanes: Jürgen from then on in his own airplane, Günter with his son Gero as a copilot and mine. We filled the airplanes in the night to get as much fuel into the tank as possible.

In the morning darkness, the general aviation area was completely locked up so that we had to "climb over the fence" to get to our airplanes. As the tower was not yet occupied, we taxied to the runway, reporting by radio on our ground movements as is usual in the USA. An air freighter started opposite to our take-off direction and then it was our turn. We took off towards the sea, communicated with San Francisco Center and were finally given ocean clearance. We had a tremendous flight of 14 hours. With a head wind in the beginning, our fuel computer continuously indicated "not enough fuel to destination". But we had a lot of time to reach the critical point of return and when we finally reached it, the wind had veered round as expected. Flying at low altitude, we were pushed forward by the trade winds. Paul, a pilot we met in Santa Barbara, has covered this distance as many as 312 times, always at an altitude of 6,000 ft assisted by favourable trade winds after travelling half the distance.

In Honolulu our 360° friend Willie and his wife Lily hospitably received us and we spent a restful day visiting the city and enjoying Waikiki Beach. We then took off at 0400, our airplanes filled up for the next long leg of 2,070 NM to Tawara (Gilbert Islands). Weather was fine and pushed forward by tail wind, we were approaching the place of my trauma....

Approximately 220 NM before Tawara, at 10,000 ft., there were heavy clouds, which we flew round making use of the weather radar. I was just evading a moderate to heavy (green-yellow) turbulence area, when I got a heavy but short blow of turbulence. Afterwards, everything was quiet again. Obviously, radar was unable to detect this wind sheer.

Suddenly, I detected a scorched odor. In the past, that had always been caused by electronic instruments, but now I could not find any fault and it did not smell the way it did in other cases. Before I finalized my check-up, there was a heavy metallic blow in the engine compartment and dark clouds of smoke in the cockpit. I opened the window for fresh air and pressed my nose and eyes against the small opening.

Then I realized that the smell had been hot oil leaking somewhere. (I still had my oxygen mask on)! The engine stalled; although I was able to restart it, the power produced was too low. Oil pressure had dropped to 0 psi, oil temperature to 0°C. The Graphic Engine Monitor (GEM) indicated that all cylinders on the copilot's side had failed. At low power, the motor would run, but I was unable to maintain the altitude. With alternative power settings, the engine would vibrate so much that it risked being torn from its mounts.

I had no alternative but alighting on water. Going down in a glide, I continuously transmitted my position, put the life raft on the copilot's seat and my personal survival canister on the floor, set the electronic satellite position signal unit (EPIRB) at 406 MHz, all the while flying the plane under IMC conditions.

At about 300 m (approx.1,000 ft) above sea I was below the clouds and could see the very smooth sea - the world's largest landing runway appeared ahead. I left the landing gear re-tracted, transmitted my GPS position, set the landing flaps at 15° and touched down so smoothly that the airplane bounced like a flat pebble. The right wing and the tip tank plunged in first, followed by a short, hard whirl tearing off the right tip tank. My left shoulder was pressed against the wall of the cabin which prevented my being injured. Water was splashing through the small pilot window. My glasses blew off and the airplane was swimming. I opened the door - it was not jammed - threw out and activated the life raft and threw my personal survival canister aboard.

At that moment, the airplane began toppling over and after about 10 seconds, it began to sink. I jumped into the life raft. However, my EPIRB was still in the airplane, although secured to the life raft. My efforts to loosen it were useless, the line had been caught somewhere. The airplane tail threatened to hit me and the raft, so I released the line and pushed the raft away. About 30 to 45 seconds had passed.

As the line to the EPIRB caught in the cabin threatened to draw us down or destroy the raft, I had to untie it. Then the airplane, with this vital position signal device, disappeared in the sea. The survival set supplied with the life raft also disappeared. Obviously, the cable fastener was not strong enough. After about one minute, the whole airplane was under water.

Jürgen flew towards the position I signalled by means of the portable air radio I had in my survival canister, which transmitted my GPS position on emergency channel 121.5. I reported that I was unhurt, though harmed in my mental state, which somewhat relieved my friends. Gero informed Honolulu by short-wave about what had happened.

Jürgen was reluctant to leave me and kept flying above me to establish my position. Unfortunately I forgot to tell him that the EPIRB had sunk with my airplane. Jü'rgen then received the information that a ship would be coming from Tawara to pick me up in about 10 hours - but how should they be able to find me? (I came down at 16:06)

I had to protect myself from cold and therefore took the tent and two rolls of coated aluminium out of my survival canister, wrapped myself up in the covers and kept the air and marine radios on hand. The marine radio with its extremely high battery capacity and wide channel capability also had channel 16 which is the international emergency call channel that all ships have to keep open just as airplanes have to keep the 121.5 channel open.

During the night I could not make out any activities, but hoped to see something in the morning. According to my GPS, I was drifting approx.0.8 NM/hour south-east with wind coming from northeast, with heavy current, away from my landing place at 30, 24.5' N 176 15.8' E and the islands.

I called Mayday each hour by the air and marine radios, but I wasn't heard by anybody; there was no reply. From 16:00 (24 hours after ditching) my hopes were dwindling away and I thought my last hours had come. I apologized to my family and friends for all my doings and went to sleep in my huge waterbed, swearing to myself that I would never give up - and waiting for a miracle.

At 17:00 the miracle came: a 4-engine military aircraft (P-3 Orion) was flying above. I quickly took the radio, saw the aircraft disappear in the sky and kept calling "Mayday, Mayday, Mayday..." on channel 121.5 - and they actually responded! "This is AUSSI 130 on a measurement flight!"

"Please come back," I cried, "you have just flown past me, a pilot in a life raft, Mayday, Mayday, Mayday!" They returned, following the position information I gave them, saw me and then everything took its professional course. They dropped several sonar devices and smoke bombs with fire every 15 minutes. I felt such a great relief that I burst out crying. I could hardly believe my luck. It became darker and darker, but I had my small flashlight (Mag Light) which helped the aircraft crew to locate me. A trawler was not far from me but as it did not respond to their radio call, it was not obliged to help. (I wonder what its nationality was.)

The aircraft crew told me that a patrol boat was approaching from the Marshall Islands where it had left the port approx. 3 hours after my landing. It had to cover as many as 380 NM to reach me at about 0100 that night (which was the second night in the raft).

Six hours later the military aircraft left me and returned to its base because it was short of fuel. They informed the patrol boat that they could reach me on marine channel 16 and that I was able to signal my position by GPS. "We know everything about you," they told me when I attempted to tell them my radio number. "At the moment, you are the most important person in the Pacific!"

It was getting darker and darker. Freezing I tried to wrap myself up in the plastic covers while pouring back the water coming into the raft by using the small bailer (shovel) I had in my survival canister. Would the radios hold out? The marine radio with GPS to signal my position was vital to me. I still was freezing, vomiting and summoning all my strength. At last, the patrol boat was arriving. I continuously signalled my GPS position, and the last mile they could see my small Mag Light flashlight. I did not need the signal rockets.

The crew of the RMIS Lomor helped me to get on board. Still dressed, I took a hot shower, then washed my clothes and gratefully and exhausted fell into bed. My feelings were completely mixed up. During the trip back to the Marshall Islands, which took 2 days, I was able to talk with Jürgen and Günter who had had news lonesome me did not have, of course. They told me that because of my hourly signals on channels 121.5 and 16, the Americans had directed a satellite at me which had been able to locate my radio messages so that each hour they had a computer printout of my position and drift. But how could I have known that?

I was well cared for on board and after 13 hours of sleep I was soon feeling better. Jürgen, Günter and Gero who were waiting for me on the Marshall Islands were happy to see me.

They had already arranged for my flight back to Germany - without my passport, mind you! I declined with thanks Jürgen's offer to continue the 360° trip as his copilot;I felt this would exceed my current mental strength and would be unfair to my family. I therefore got into the airliner back to Germany, while Jürgen and Günter continued on in their V35Bs to complete the 360° round. But their feelings had changed, too. The person responsible for the rescue operation was Mr Nada from the Fiji Islands. Jürgen and Günter persuaded Mr Nada on Nadi to ask Australia for help.

The aircraft above me was a P-3 Orion which normally is a sub chaser. Lieutenant Commander Hans von der Zyden controlled all activities from Tawara. After talking to Captain Piersen who managed the operation from Honolulu, Lieutenant Commander Hans van der Zyden was able to receive my EPIRB on 406 MHz for a long time and to record its position and drift. As the EPIRB is not able to operate when it is more than 3 ft below water, it must have wound its way through the open cockpit door of the sinking airplane to rise to the surface and activate itself (by sea water). Thus it must have been swimming somewhere near me. Its distance from me had only been caused by the wind drift.

I herewith wish to express my sincerest thanks to all those who helped me survive that distress at sea!

is reproduced with the permission of American Bonanza Society. http://www.bonanza.org

1 box with first aid drugs

16 x aspirin

8 x antihistamine

12 x anti-motion-illness

8 x throat lozenges

4 x antidiarrheal

8 x antiacid

10 x salt/electrolyte

2 x ammonia inhalent

1 x first aid cream

4 x anti-septic towelettes

10 x sheer strips

4 x gauze pads

1 x sanitary napkin

1 x adhesive tape

1 x gauze roll

1 x elastic rubber bandage

4 x butterfly wound closures

1 x moleskin protector strip

1 x toothache kit

2 x sun glasses, emergency type

2 x Iight sources

1 box, CuPlstorage container No. 1

2 x lemon drops PKGS I3EA

6 x tea bags

6 x sugar bags

1 x water purification tabs

3 x fruit drink mix

1 x soap bar

1 CUP / Storage container No. 2

6 x dry cereal bars

4 x soups

2 x chewing gum

1 x toilet tissue

1 x tube tent

1 x emergency/survival handbook

2 x polarishield emergency blankets

3 x BP-5compact food, 500g - 2,290 ccal.

Seawater desalination kit PUR Survivor 06, approx. 1 l/h:

1 x four-season waterproof sleeping bag cover - new in the canister

1 x waistbag

1 x strobe flashlight, waterproof1 2 km visibility, flashing 20 h

2 x mosquito head net

1 x hatchet

1 x reading glasses (new in the canister)

1 x distance glasses

1 x Leatherman tools

2 x aluminium-coated isolating life wrap

1 x headgear

10 x Lithium AA batteries

1 x Gamin GPS 45 x 6, waterproof

1 x waterproof cover for the radio set

1 x Swiss army pocketknife, emergency set

2 x 0,5 l plasfc bottles, empty - for making water

1 x bauer (shovel)

1 x Nivea suncream, protection factor 26

1 x Drantronik-lcom GM 1500E marine radio set

1 x Drantronik-lcom Lithium battery CM-176

1 x Drantronik-lcom aircraft cable

1 x ACR satellite 406 MHz EPIRB, D-IBEL registered

1 x air radio set + GPS, BendixiKing KLX 100 (8 x AA batteries)

2 x sponges

2 x Mag-light flashlights

1 x burning glass

1 x compass

1 x sewing kit

1 x Isolation tape

20m rope, 3mm

1 x working gloves

20m rope, 1 ,7mm

30 cm plastic tube - (for drinking water out of holes)

20 Micropur tablets (water desinfection)

- isolated life wrap

- First aid bag

1 compress

1 quick dressing

1 finger dressing

1 cloth compress

1 aluplast assortment

1 WS elastic bandage

5 plaster strips

1 lifewrap

NOT IN THE CANISTER

Life raft, Survival 4 persons, Klemann & Kreutzfeldt GmbH, 19260 Banzin/Germany

"SEAMATE / FAR 91"

- Survival suit

- ACR Mini B2 EPIRB 121, Sand 243 MHz, 48 h

Life jacket, belt-type

Standard life jacket

.gif)

The site of the Equipped to Survive Foundation. Information on methods and sources for survival.

The site contains a story of survival at sea very similar to Horst's and is well worth reading :

http://www.equipped.org/1199ditch.htm

Contact us in English, French, German, Spanish, Italian or Portuguese:

Copyright © Claude Meunier & Margi Moss, 2000 -

2026

|